Over the past 15 years, national policies aimed at reducing inequalities in access to higher education in France have produced real results. Encouraging ? Sufficient ? Still improving ? While it’s not our place to judge the current situation, we’d like to open this issue with a general observation: progress is being made !

For example, nearly 40,000 students with disabilities are now enrolled in higher education at university, school or lycée. This corresponds to a 30% increase in enrolment in 5 years (end-2021 figures), while the number has increased 5-fold since the 2005 law and 2.5-fold since the 2012 university-disability charter.

But inclusion is not just about access for people with disabilities. It also concerns students’ social situation, their membership of a minority, whether ethnic, cultural, or of a sexual orientation, and sometimes even their geographical location. What’s more, some students face other serious difficulties, such as discrimination, social exclusion, harassment or lack of resources, and may therefore be at a disadvantage in their academic careers.

In France, under the impetus of the Ministry of Higher Education and Research, the national monitoring committee for inclusive universities is ensuring that all players provide solutions for the accessibility of training courses, student life in all its dimensions, digital environments, content and compensation measures (human assistance, technical assistance and examination arrangements).

At European level, the European Commission is presenting recommendations to its 27 member states, stressing that “higher education must contribute to meeting Europe’s social and democratic challenges”. Three major avenues have been identified for achieving global harmonization of study paths :

- a comprehensive approach to admission, teaching and assessment ;

- take measures to ensure student tutoring ;

- provide both academic and non-academic support.

Naturally, we’re talking here about inclusion in the broadest sense, aiming for an equality of opportunity that still seems a long way off for certain populations. The EUROSTUDENT study carried out over 2018-2021 at European level, indicates that 15% of students suffer from a “physical or psychological disability” and that 15% of the student population has an immigrant background. Responding to better integration of these two minorities and guaranteeing them equivalent access and results remains an essential challenge, including when disparities between countries are appreciable.

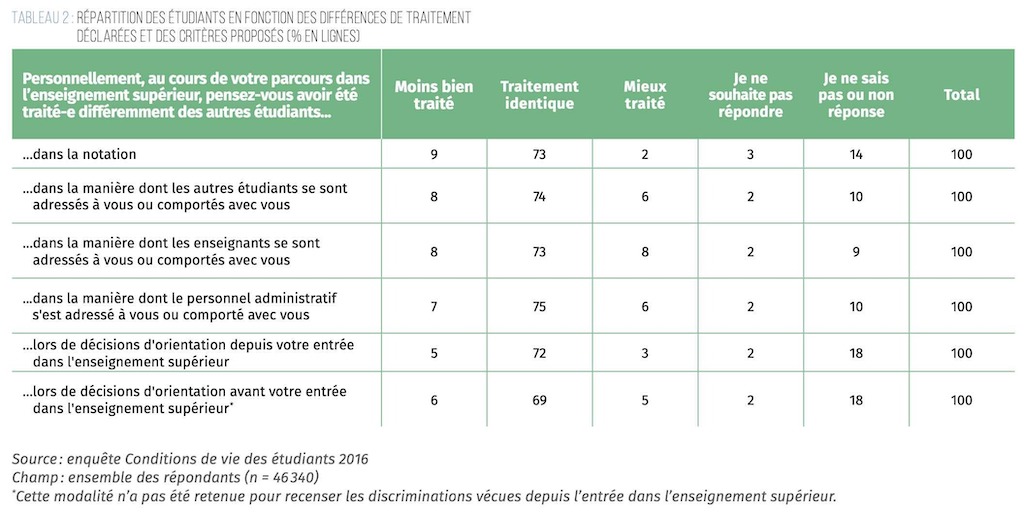

In France, a survey by OVE (Observatoire de la Vie Etudiante), revealed in 2016, that almost 20% of students said they had been “treated less well” than their peers within universities. This percentage rose to 28% when students whose parents were both immigrants were surveyed, and to 30% when the student was of foreign nationality. It’s also worth noting that 19% of women felt less well treated, compared with only 17% of men. Among students who felt less well treated, the student experience was a key concern, with 14% feeling “not at all integrated into their group or class”, while 21% felt “not at all integrated into the life of the institution”.

It is important to note that only one student in 8 is able to identify the cause of his or her “bad treatment” in relation to others, and disability or gender are not given much prominence. On the contrary, origin or nationality seem far more significant when it comes to explaining a difference in acceptance by the system. Finally, for those who didn’t necessarily find a primary explanation for their feelings, the study underlined that social attitudes and behaviour – whether in terms of politeness, social ease, dress conformity or sporting or cultural practices – were also a source of discrimination.

While acknowledging that the situation is not optimal is a step forward, inclusion means taking diversity into account and respecting it, but above all responding to it.

So what are the main ideas for improving student inclusion in their course of study ?

Diversity is defined in this way by two researchers from Quebec’s Laval University, Sheryl Burgstalhler and Rebecca Cory :

“It implies the variety of identity markers of individuals and groups. It also refers to the attitudes, modes of expression, experiences and needs that arise from these different characteristics: communication skills, culture, marital status, ability to be present in class, learning abilities, intelligence, fields of interest, cognitive abilities, values, social skills, family support, learning styles, age, socioeconomic status, religious beliefs, sexual orientation, ethnicity, physical and sensory abilities, ethnic group, gender.”

What are the main difficulties encountered by learners at all levels, and which characterize this diversity?

Their work by Sheryl Burgstalhler and Rebecca Cory is taken up in the Universal Design for Learning, which proposes three main principles for increasing inclusion, based on the variety of means of representation, action and expression, as well as engagement.

In a way, the multiplication of modalities of presentation, expression and evaluation now made possible by digital tools and platforms should go a long way towards improving the situation. But digital technology must not be allowed to exacerbate the inequality of access to knowledge.

Digital Edtech as a factor of inclusion ?

French EdTechs are working in this direction, and while they all have in mind the difficulties experienced by certain student populations, a few have made inclusion their flagship subject. Take Cantoo, for example, which targets young people suffering from written language disorders (dyslexia, dysorthographia and dysgraphia), or Colori, which helps children to better understand the digital world without resorting to the screen, targeting QPVs (priority urban policy districts) and girls in particular. These initiatives are supported by Banque du Territoire, as is My Future, which helps young people from disadvantaged backgrounds to find internships throughout their apprenticeship.

What about higher education staff ?

However, it would be simplistic to confine our discussion of inclusion to the student population. The issue is also a major one within higher education establishments. Do educational staff feel perfectly integrated, while respecting their diversity ?

Figures recently published in an article in EdTech Actu show that much remains to be done on this subject, even if the situation has evolved positively since the 2005 law. For example, in 2020, “higher education had an average rate of 3.5% of staff benefiting from the employment obligation (BOE), i.e. with a declared disability, compared with the minimum 6% of staff required of each administration by law.” There are major disparities from one establishment to another, even though a disability correspondent has been appointed in every French university since 2005. Cyril Garnier, senior vice-president of FNCAS (Fédération nationale pour la responsabilité sociétale & Conseil en action sociale – enseignement supérieur, recherche), a lecturer and researcher at UPHF (Université Polytechnique des Hauts de France), agrees :

“It’s more than just raising awareness, it’s a real investment in disability. This is increasingly part of their governance strategy, as it contributes to their direct attractiveness.”

In a book entitled “L’envers de l’école inclusive” (The other side of inclusive schooling) published in November 2022, school teacher Magalie Jeancler analyzes the questions and problems raised by inclusive schooling, which refers to the integration of children with disabilities into normal classes. She underlines the loneliness of teachers faced with the pedagogical challenges posed by this approach, as well as the lack of appropriate support.

Clearly, the challenges of inclusion begin in the early years of schooling. The consequences of a lack of resources deployed to promote inclusion from the outset are likely to be far-reaching once pupils have become students. There are many voices expressing growing discontent in our country, and some are vigorously challenging our governing bodies. For example, the “Inclusive School for All” collective, which brings together parents, teachers and AESHs (the staff who provide support for pupils with disabilities), organized a demonstration in front of the Palais Bourbon on Wednesday March 29, to ensure that “every child with a disability benefits from schooling adapted to his or her needs”.

France is a country whose education system is faced with complex situations, and in particular with ever-increasing demands for access to success for all. Inclusion is undoubtedly a major theme in the development of a desirable future for higher education. Once again, universities are on the front line in guaranteeing the republican spirit and equal opportunities. This noble mission can mobilize our entire ecosystem to find new solutions and respond to the diversity of the student world.

Want to know more about digital in higher education, EdTech news and so much more you could yet discover about digital transformation ?

There’s only one thing to do: register here, and we promise that if a robot invasion is on the way, you’ll be the first to know !

https://www.simoneetlesrobots.com/communiquer/