Are universities really lagging behind in their digital transformation, as some media may imply?

In March 2020, in the space of a week, they had to face up to an unprecedented situation, during which they proved resilient and efficient, putting in place solutions to ensure pedagogical continuity for all their students, in a secure manner

This crisis situation must remain exceptional in the collective mind, and must not become a reflection of the progress made by universities in the digital field. Videoconferencing platforms, about which everyone talks a lot, are only part of the spectrum of educational technologies, and their widespread application to all students, over the whole academic year, is not a pedagogical objective. It’s important for Simone’s Robots to recontextualize these subjects, and to highlight the resilience of universities.

While French establishments have been somewhat heckled by the media, which have sometimes rightly reported that they are lagging behind foreign countries, where do we really stand?

Universities in constant evolution!

The issue of digitalization, and the associated transformation of the organization, was already present in universities long before the Covid-19 crisis.

In particular, the need to adapt to a new public, accustomed to the flexibility, connectivity and rapid access to information afforded by the technologies they use every day, as well as the need to educate, advance research and facilitate professional integration, pushed universities down the path of digital transformation many years ago.

The University of Rouen, for example, was one of the pioneers in the use of video, installing a video portal back in 2011! Since then, the university has been equipping and improving this technology, which today has become a real asset. With classrooms equipped with video capture solutions, it’s easy to create teaching content that’s available both synchronously and asynchronously, according to the wishes of the teacher and the needs of the students.

This system provides great flexibility and ease of access to learning content, enabling everyone to personalize their learning. And as we’ve already mentioned several times on this blog, the effectiveness of video content has been proven. Today, video is the most consumed media format on the Internet. That’s why it’s so important to learn how to master it, to get the best out of it, especially in terms of engagement.

In parallel with the acquisition of commercial solutions, and for many years now, certain universities have been coming together to innovate. Such is the case of the ESUP consortium, which was formed in 2002 by 5 universities responding together to a ministerial call for proposals, and since 2008 has been an association of over 80 French higher education establishments keen to contribute to the development of innovative digital solutions.

Since the initial virtual learning environment project, ESUP has led several significant projects for the digital transformation of public higher education, notably around single sign-on, electronic document management and collaborative working, paperless applications and recruitment, and student communication. More recently, in 2014, at a time when YouTube was already in full swing, the POD video hosting and distribution platform, perfectly in tune with the new needs of students, was created by Nicolas CAN at the University of Lille. It is now supported by ESUP.

In parallel with the development of digital solutions, the most innovative universities are also offering their students and researchers Digital Learning Labs, comprising spaces equipped with high-performance technological tools for experimenting, researching, testing and applying their knowledge. To name just a few, the most curious can visit those at the universities of Tours, Caen, Orléans, Nantes, Lyon 3 and Sorbonne Paris Nord! But there are many more …

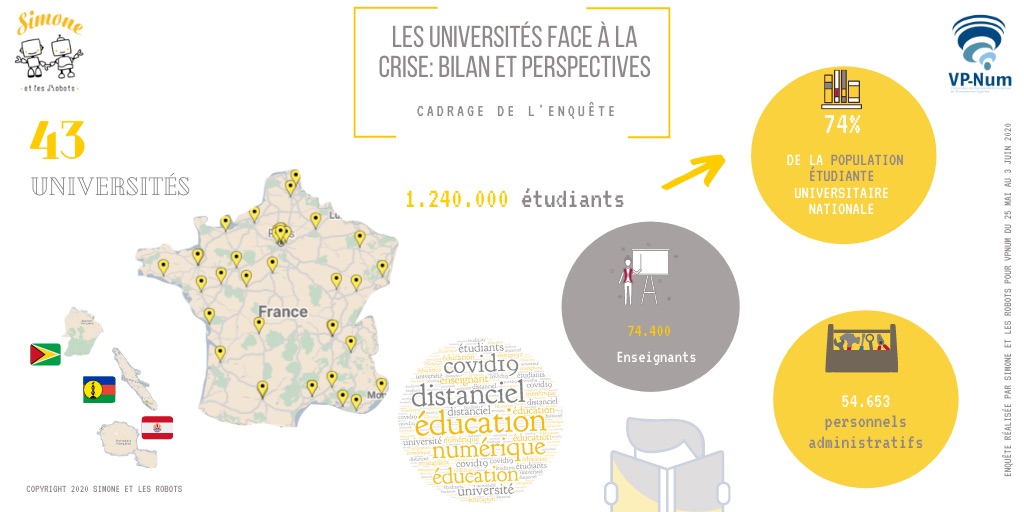

Against this backdrop, it comes as no real surprise that, in our survey for VP-Num carried out in May 2020, we noted that 98% of universities already had a Moodle LMS, and that most of them were using Teams, Big Blue Button and Zoom for distance learning courses. With the crisis and confinement, connection volumes increased considerably, but most solutions were already installed. As Brigitte Nominé, Vice-President of Digital Strategy at the University of Lorraine, reminds us in our #Univ4Good interview :

“In the first few weeks, we went from 20,000 sessions to around 70,000 sessions a day. The Digital Department adapted server capacities and parameter settings so that things stabilized and we achieved completely satisfactory use of the platform.”

Universities’ ability to propose solutions to facilitate distance learning has thus had to be accompanied by an ability to upgrade infrastructures to enable the simultaneous connection of several tens of thousands of students. Against this backdrop, CIO and DN teams have demonstrated their ability to adapt, mobilize and remain resilient.

On the human side, teachers have also largely mobilized, as Thierry Spriet, VP Digital at the University of Avignon, confirmed to us in July 2020:

“We switched almost all our teaching to distance learning, in a variety of ways. Naturally, each teacher has been an active participant, deciding on his or her own method and approach.”

So what difficulties have universities encountered during the crisis?

The real problem created by this sudden and unexpected crisis stems from what is commonly referred to as “scaling up”. As we have seen, the tools and methods were already in place on a massive scale.

And yet, in this crisis situation experienced by universities the world over, it was necessary to massively switch the entire student body and teaching teams over to a distance learning format. Tens of thousands of students were thus urgently redirected to videoconferencing platforms and LMSs capable of handling large volumes.

This situation has now lasted for over a year, and distance learning is no longer just a crisis tool, but a genuine new way of teaching. It’s clear that it’s no longer enough to simply transpose physical courses into digital form, but that a whole environment needs to be recreated around distance learning to ensure that teaching remains attractive and dynamic. New forms of pedagogy must become widespread, placing students at the heart of their learning.

Teacher support: the second major challenge for universities.

In the same interview, Brigitte Nominé explains how the university took account of this upheaval in practices from the very first weeks of the crisis: “We set up webinars for teachers who were unfamiliar with the Arche (Moodle) platform. We then specialized the themes of these webinars, which were attended by almost 600 teacher-researchers.” But there is no doubt that we need to look more closely at the changing role of the teacher, who has been asked to play a much more active role in supporting students. Disseminating knowledge via digital platforms is not enough, as knowledge needs to be patiently explained.

The role and missions of the teacher are changing, and as Thierry Spriet points out:

“We should rather imagine that a teacher has a certain share to take in a student’s learning. This share could be expressed in ECTS credits, for example. It’s up to the teacher to decide how he or she is going to use the credits. This could be face-to-face, distance learning, synchronous or asynchronous. We’ve seen that there are lots of ways of teaching, and much more than just face-to-face with students.

An approach very similar to that used in Belgium, for example, and particularly at UCL.

Certaines universités ont également profité de cette période atypique pour tester des outils numériques favorisant l’interactivité durant les cours.

L’université de Limoges par exemple, propose à ses enseignants un tutoriel pour rendre ses cours plus ludiques avec Wooclap :

These new learning experiences also raised new expectations among students. Beyond access to course content, a whole range of solutions had to be developed rapidly.

Digital investment has therefore expanded into student services, such as collaborative platforms or mobile applications that simplify remote working, or create spaces for exchange outside the physical spaces of the campus! Personalized mobile applications, such as Campus M or AppScho, offer the possibility of creating a stronger commitment between players in the university ecosystem by giving them a means in their pocket of accessing information, exchanging ideas, or even interacting with campus infrastructures by reserving a place in the library.

But if universities were offering certain services before the crisis, it was only during the crisis that some teachers tried out new, more connected practices. To compensate for the lack of interaction and the monotony of a zoomed-in lecture day, they experimented with connected classrooms, video capture solutions and interactive exercises, enabling them to innovate and give their teaching a little more perspective. It’s worth noting here the resilience of the teachers, who have been able to renew themselves, listen and adapt as best they can to improve the student experience. And it’s by testing that they’ve been able to discover their own needs, and it’s thanks to their feedback and investment that universities and EdTech solutions have also been able to make progress in responding to these new needs.

For over a year now, universities have shown tremendous resilience under extreme conditions. They have been able to set themselves in motion, adapting the digital means and resources they already had, and rapidly integrating new technical solutions. The acceleration that all players in the EdTech sector are calling for is very real, particularly in the implementation of technologies that enable knowledge sharing and permanent links between teachers and students. Of course, as with any change, there has been a great deal of support, and much remains to be done to make practices more fluid. Other initiatives have been developed in various foreign countries, and here too, active international monitoring will undoubtedly enable us to draw inspiration from advances in pedagogical hybridization. In a future article on this blog, Simone’s Robots will present some remarkable success stories in this field.

However, it is objectively realistic to take a positive view and maintain this dynamism for the future. Indeed, French universities are already examining all the possibilities offered by EdTech, to enhance pedagogical performance and maintain a strong relationship of trust within public higher education. It remains to be hoped that more upstream collaboration between EdTech and universities will see the light of day, as is the case in the northern European countries mentioned in this article.